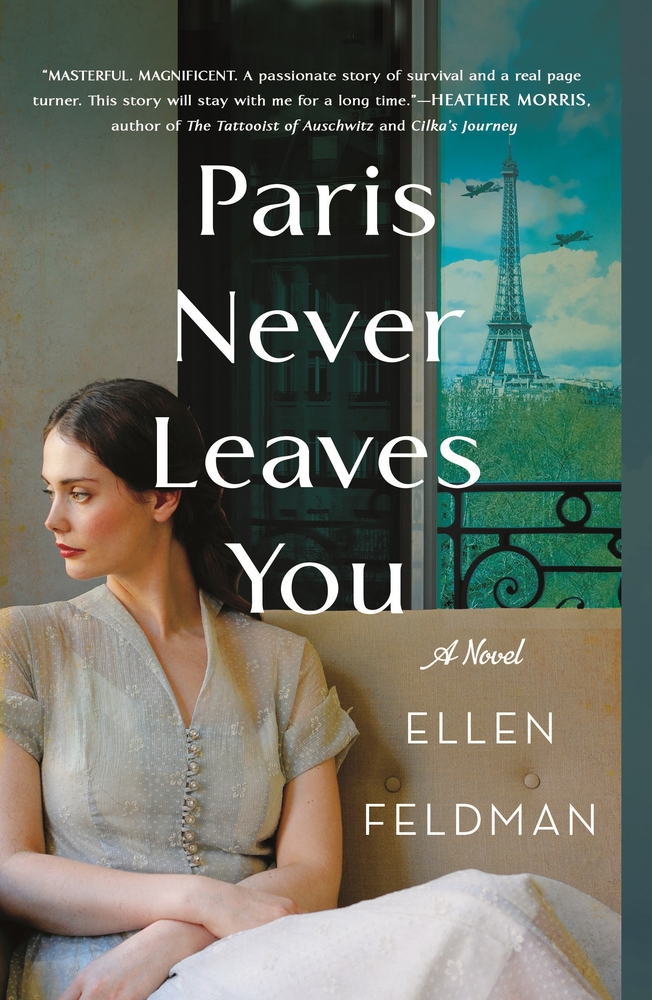

If you’re looking for a new book to add to you reading list, Paris Never Leaves You could be just what you’re looking for. The goes between WWII France where we meet Charlotte Foret who works at a bookshop in Nazi-occupied France. runs a bookstore to 1950’s New York where Charlotte now works for a publishing company. If you’re a fan of Kristin Hannah’s The Nightingale then you’ll definitely want to add Paris Never Leaves You to your bookshelf!

In this interview, author Ellen Feldman gives us an inside look into the novel, sharing when she first came up with the storyline, the research that went into the book, who she would like to play Charlotte if the novel were to be adapted into a feature film and more.

When did you first come up with the storyline for Paris Never Leaves You?

I’m not quite sure when I started to think about the storyline, but I do know how I began to think about it. The inspiration for the book came from Charlotte, and the inspiration for Charlotte came from women who were nothing like her. As I read memoirs, biographies, and accounts of WWII, both for pleasure and for research, I came across many women who spied for the Allies or fought for the Resistance or risked their lives as war correspondents. And the more I read, the more I began to wonder about women who were not blessed, or cursed, with their courage, women, I admit it, like me. How would they manage to eke out a normal life under horrendously abnormal conditions? How would they navigate a world stalked by danger and threatened by shortages of food, medicine, other basic necessities? How far would they go to survive? What compromises would they make? What moral corners would they cut? And as I thought about these questions, an even more dire one occurred to me. What would that woman do to save her child?

At what point during your time working in the publishing industry did you start writing your first novel?

I started writing my first novel after I was fired at the Christmas party, which is a story I tell in a piece for Literary Hub. Before that event, which turned out to be not nearly as disastrous as it sounds, the editor-in-chief of the house, whom I admired greatly, had recommended that I quit my job publicizing other people’s books and go home and write my own. The suggestion was tantalizing but impractical due to the fact that I like to eat and prefer sleeping in a bed rather than on a park bench. Then at the fateful Christmas party, the choice was taken out of my hands.

About a week before Christmas, at another party for a book I no longer remember, I was chatting with a popular and critically acclaimed writer who also happened to be a notorious womanizer. (Taking care of celebrated guests was part of my job as director of publicity.) I don’t remember being offended by whatever it was he said. In those unenlightened days, sexual predation was still an accepted form of flattery. But I do remember wanting to discourage him without insulting him. I told him that though he might be a male chauvinist pig – the terminology of choice of the day – he was a charming male chauvinist pig. The secretary to the publisher was passing as I spoke and heard the words but not the tone.

The next morning she reported to the publisher that she’d overheard the director of publicity calling one of the most renowned writers of the day a male chauvinist pig. A week later, at the holiday party, the publisher gave me my Christmas bonus in the form of a metaphorical pink slip. I’d like to say I went home and wrote my first novel. I did, but months of toiling as a freelance copywriter while I worked on the novel and struggled to get it published undermine the fairy tale gloss of the story.

The storyline goes between Paris during WWII and 1950’s New York. What drew you to this particular time period?

I’ve always been fascinated by WWII. I’m a firm believer that our memories go back to the events our parents lived through. My mother talked about the war as I was growing up. My uncle, who served as an army surgeon in England and France, never quite got over his experience.

As for the 1950s, though I was too young to know it at the time, I was a beneficiary of postwar prosperity and optimism. It was an era when America was a land of more equal opportunity. The GI Bill gave men, and a handful of women, who never could have dreamed of college or afforded it, the chance to earn degrees. It also enabled them to buy homes and start businesses. Unions insured many workers a comfortable middle class life. It wasn’t all sunny. The women who’d worked during the war were sent home. Not all of them were happy about it. In fact, the daughters of those disgruntled women made the feminist revolution of the 1970s. Racism was widespread, virulent, and shameful. But like the women who’d found new freedom during the war, the Black GIs who’d fought for America and found greater acceptance in other countries were planting the seeds of the Civil Rights Movement.

How much planning do you do before you start writing?

I don’t so much plan as let the research lead me. I usually begin by reading general histories of the period, then go on to personal memoirs, magazines and newspapers, and archival material. I love getting lost in libraries, and I love the thrill of coming across a little-known or previously unknown letter or diary entry or scrap of paper that brings the character or period to life. In a more general sense, even the ads in old newspapers and magazines can untether you from the present and pull you back to another time.

Of course, libraries can lead you off on tangents. Some are distractions. Others are invaluable serendipitous discoveries. I had the latter experience with Paris Never Leaves You.

I do much of my research at a wonderful subscription library in New York City. One of its myriad attractions is open stacks. One afternoon I took the archaic wire cage elevator down to the stacks looking for a particular book on Paris under the Occupation. The title on the spine of another book caught my eye. It indicated something I’d never heard of, nor, I later learned, had many historians I spoke to. (I won’t say what it was here, because I don’t want to give away the plot.) I was so fascinated that I sat on the floor of the stacks and began to read. Two hours later, I emerged from the stacks with a very different conception of the book I was going to write. One character had changed drastically, and the moral issues were suddenly far more complicated than I’d thought.

On the other hand, for some aspects of the book, like life in a publishing house, I had to do no research at all. While the business had changed by the time I was fired at that Christmas party, human nature hadn’t.

If you could talk to Charlotte in real life, what would you like to say to her?

That’s a fascinating question. I think I’d tell her the same things Horace does in the novel.

What was the most difficult chapter to write?

They all seem difficult when you’re writing them, but there’s no doubt that some are more recalcitrant than others. The scene of Charlotte and Vivi hiding in the back of the bookshop during the Nazi roundup was probably the hardest for me. I usually find action scenes more difficult to write. This is not to say that the scenes of emotional or psychological conflict come easily, but I do find them more intriguing, and as a result rewriting or revising them tends to be more fun.

If Paris Never Leaves You was turned into a movie, who would play Charlotte?

My choices, not necessarily in this order, would be Keira Knightley, Gemma Arterton, or Juliet Binoche.

One of your earlier novels, The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank has been translated in nine languages and Terrible Virtue is being adapted into a Feature Film. How did you feel when you received the news that one of your books would be brought to the screen?

This question makes me smile – at myself. My first reaction was euphoria. For a while after that, every time I went to a movie, I saw my name appear on the screen. “Based on the book by Ellen Feldman.” Gradually, I remembered a warning I’d read by Hemingway years ago. It concerned instructions for what to do when you sell your book to the movies. Drive to the California state line. Ask them to throw over the money. Count it. Throw over your book. Get back in your car and drive like hell. That said, when I met the head of the production company that bought the book, I was impressed by her insight and intelligence and delighted with her vision of the book.

You’ve given lectures both in Europe and the US as well as giving talks for book groups both in person and virtually. What do you enjoy the most about talking to fans of your books?

The Q&As are definitely the best parts of talks. Readers can be surprisingly canny. I love it when a reader makes me see something in the book that I hadn’t even realized I’d put there.

Are you currently working on your next novel, and if so could we get a sneak peek?

I’m always at work on a new novel. Friends and loved ones tell me I’m not much fun to be around when I’m not writing. The new book came out of an anecdote I came across in the research for Paris Never Leaves You. The incident and its repercussions just wouldn’t let me go. This time the book is set in America before the war and Berlin under the allied occupation, and this time it concerns forgiving others as well as ourselves.

Pick up your copy of Paris Never Leaves You.